| June

"E-E-E-E-E-K!"

It was one of those wifely calls that tells a husband to get there pronto.

So I quit whatever I was doing in the garage and headed for the front porch.

I knew the source of my wife's stress as soon as I emerged from the

garage.

Fifteen or 20 feet from the front porch there was a huge beech tree,

and 20 feet above the earth there was a beautiful little knothole, not

quite large enough for a squirrel access to the interior of the tree which,

true to beech characteristics, had to be hollow.

Thousands of bees swarmed around the knothole and the air was black

with thousands more all the way to the open front door and my wife who

stood speechless, but safe, behind the screen door.

"Look at that . . . bees . . . " she cried as I approached the front

porch . . . "we'd better get rid of them."

"No problem," I soothed . . . "it's a bee swarm . . . they've found

a new home in our tree."

"Well, we've got to get rid of them," she insisted.

"Tell you what," I said (as reassuring as I could make it sound), "don't

look out the window for 20 minutes . . . then see what you think."

I am certain that my wife counted the minutes (perhaps even the seconds).

But when my 20-minute quasi-reprieve for the bees had expired we went to

the front door again stepped outside. Not surprisingly (at least in my

mind), we found the bees almost gone.

Actually, they were very much there. But they were inside the hollow

of the big beech, establishing a new home.

The activity at the tiny knothole, where the bees entered the hollow

of the tree, told me plenty. There was a steady stream of bees entering

the knothole or leaving, but we saw no more than a few bees (perhaps half

a dozen) at a time. Yes, they had found a new home . . . We had new neighbors

. . . It was a thing a citified country boy dreams about.

Later, when hot, dry weather took over the Midwestern summer, there

would be vast numbers of bees mysteriously hanging from the knothole, but

this was not a problem either. I didn't understand it at the time, but

I later would learn about the "loading dock theory" of the late Albert

J. "Al" Thomas, an older man, who was for many years the most well-informed

bee expert in Central Indiana. Mr. Thomas died in 1987.

"Mr. Thomas," whom I would not know until the following spring, had

grown up in downtown Indianapolis. His father had owned the C. M Scott

Company, a bee keeping supply firm in Indianapolis. He had followed his

father's footsteps, and, I (the neophyte bee-keeper of sorts) would be

enthralled on many occasions as he sat behind the antiquated wood counter

of his "store" recalling incidents and lore of bees and beekeeping.

I still apply many of his lessons when I am "working" bees, but I think

his best story was the one about traveling to the north side of Indianapolis

to put (Mr. Thomas did not think of it as capturing) a swarm of bees in

a cardboard box, and returning (box, bees et al.) to downtown Indianapolis

on a streetcar. It was one of his best explanations of the docility of

bees in swarm situations.

However, I seem to be getting the proverbial horse before the cart of

the same ilk.

I didn't know Mr. Thomas until the following year (the early 1970s),

when the bees in the old beech tree swarmed for the first time. Before

the swarm I had been contented with merely having s colony of wild honey

bees almost within spittin' distance of my front door. But when the bees

swarmed that first time and settled on the limb of a large tulip poplar

(yellow poplar to country boys), something inside told me that I wanted

those bees. I wanted a bee colony that I could think I could control. But

the bees had settled on a limb that must have been 25 feet above the ground.

Having witnessed my father's unsuccessful attempts to get the bees, I knew

it would not be easy. I also knew I could not do it.

As I recall, I looked up "Beekeeping Supplies" in the yellow pages of

the telephone directory to find Mr. Thomas' phone number. I dialed it and

Mr. Thomas answered.

I asked if it would be possible to capture this large (there must have

been two-gallons) cluster of bees. I was informed in Mr. Thomas's easy-going

manner that it probably could be done.

Would he do it? No! But he would send someone who probably could do

the job.

Mr. Thomas further informed me that I would need a hive (about 40 bucks

at that time). But he could provide the hive and I could pay the fellow

who would come to put the bees in the hive.

An hour or so later a young fellow named Saddler pulled into my driveway

in a beat-up pickup truck which carried an assortment of beehives and other

gear. I can't remember the young fellow's first name, but he looked at

the bees and opined that this would be a tough one because the bees were

so high.

I mentioned that I had a strong 20-foot ladder, but as we held it up

toward the cluster of bees it was still four or five feet shy.

In the true derring-do manner he would exhibit in the next hour or so,

the young Saddler pulled his pickup truck directly under the bees, stacked

a few boxes, placed the bottom of the ladder on top of the boxes, and hooked

the metal flanges at the wood ladder's top end over a limb that was probably

three inches in diameter. Then, with the dexterity of a Tarzan swinging

through the trees of a jungle, he climbed the ladder and lashed it to the

limb with a short length of strong rope.

That part of the chore completed, Saddler descended to the bed of his

truck, grabbed a short saw and was eyeball-to-eyeball again with the bees

in a matter of seconds.

Then, holding the smaller limb the cluster of bees had chosen as a temporary

home, he gently sawed off the limb, threw the saw clear of his truck, and

backed down the ladder with one hand while holding the tree limb (loaded

with bees) in the other.

Saddler had already placed the hive body on its base and had placed

a section of a newspaper on the grass immediately in front of the hive.

He placed limb, bees and all on the newspaper while telling me the bees

probably would go into the hive without any urging.

But when this didn't happen in a minute or two, with his bare hand he

gently brushed a quart or so of bees (probably three or four thousand)

from the edge of the cluster onto the paper. In a few seconds those bees

started into the hive opening in a dead run (if bees can run). In a short

time other bees from the cluster were on the heels of the forerunners.

In a matter of minutes the limb was bare, and the bees were in the hive.

As Saddler bundled up his gear, I asked if $20 would be sufficient for

his services. He said that was much too much. "How about $10 or $15," I

asked. Still too much, he said. "Well," said I, "I won' pay you a penny

less than $5," and we shook on the deal as I expressed my thanks for his

prompt service and expertise. I could pay Mr. Thomas for the hive later

he said, adding that I probably would want elbow-length gloves, a bee veil,

a hive tool and a few other beekeeping accessories, including a smoker.

I was a bona fide beekeeper.

[See "The Bee Man - Pictures To Prove It"

on this website.]

End of story? Not on your tintype.

I have barely scratched the surface of the beekeeping story. My effort

here is not intended as a book--nor even a compendium--on beekeeping. Rather

it is a collection of a smidgen of the information on bees that Mr. Thomas

could/did call upon to answer the questions of his many customers, and

to advance beekeeping as a path to enjoyment, and in some cases, income.

It is a minute portion of what I like to think of as: "The Gospel Of Bee

Swarms According To Mr. Thomas."

When talking with Mr. Thomas during my call for help with the bees,

I had learned that his home and business were at the same location and

that it was only about two miles from my home. When I went to pay him for

the beehive, I had dozens of questions about the tools I would need to

manage my new colony of bees.

As he answered my questions and collected the paraphernalia I would

need, it quickly became apparent that this quiet, soft-spoken man had a

storehouse of information about bees.

When I marveled at the fact that Saddler had worn neither gloves nor

bee veil (a net used to protect the head and upper body from bee sting),

Mr. Thomas informed me that swarms of bees are not pugnacious, as popular

misconception would have us believe; that they have merely departed the

main colony (most often with a young queen) to find better living conditions.

"All they (the bees) want is a new home," he said, adding that bees

in such situations will sting if they are squeezed or pressured in other

ways, but that they usually are peaceful. However, he also pointed out

that as the cluster of swarmed bees takes longer than a day to find a home

they could get testy. Incidentally, Mr. Thomas assured me that drones do

hot have stingers.

He explained that the swarming atmosphere in a growing colony of bees

is a little like a young couple who find, as their family increases in

numbers, that they need a larger house. This often occurs when the current

"honey flow," a period in which many plants and trees are blooming, suddenly

ends. In such situations, there is less demand for worker bees and crowding

can induce the natural urge to swarm. The spring honey flow ends toward

the middle or end of May in most Midwestern states when the first big bloom

of trees and wild plants winds down. Summer-blooming plants offer a good

flow of nectar, but it seldom is as good as the spring flow.

As living conditions in a bee colony become crowded, the worker bees

fashion queen cells that look somewhat like a peanut made of beeswax. An

undeveloped worker bee egg is sealed in the cell with special food known

as royal jelly, and the egg hatches to develop into a queen rather than

a worker bee or a drone.

However, Mr. Thomas also told me that a new queen might be produced

by a colony of bees for purposes of supersedure of the queen if she failed

to produce good patterns of brood in the brood chamber of the hive.

The brood chamber of a hive is rather half-moonish in shape and will

most often be found on both sides of central frames. Ordinarily there are

10 frames in a bee-hive.

Almost all of the outside frames of a beehive will be used for storing

capped honey, but the area outside of the brood chamber proper is often

used for storing beebread, a yellowish mixture of honey and pollen stored

with larva for food. When capped, the surface of worker bee brood cells

will be even--somewhat like the appearance of a frame of capped honey.

Drone brood cells show up as individual rounded domes because drones require

more space than workers.

Queen bees are longer than worker bees (all workers are females) or

drones which are huskier that workers. Drones have square sterns and are

somewhat larger than workers. The queen must have larger body because she

must produce hundreds of thousands of eggs in her task of perpetuating

the colony. The average age of a worker bee is very short because its duties

of bringing in pollen and nectar are demanding and hazardous.

Mr. Thomas told me that I probably would not have to worry about my

bees swarming that first summer, but that this could be a problem down

the road. He said I should inspect my bees about once a week to learn how

they were faring and how the queen was doing at producing brood.

That seemed as though it could be a bit of a chore at first, but before

many weeks had passed I learned that taking a beehive apart and observing

the workings of the bees was a form of therapy for a tired body and mind.

But, as Mr. Thomas advised, the best time to work with bees is the hot

part of the day when great numbers of bees are in the field gathering nectar

and pollen.

"If they are not at home you don't have to worry about them," Mr. Thomas

would say with a wry smile.

An important reason for periodic inspections of a beehive revolves around

the fact that the beekeeper must provide enough space for the storage of

honey to keep worker bees from usurping brood chamber space for that purpose.

If the bees obviously need more space for storing honey, a queen excluder

is placed between the hive body and a super, which is a carbon copy of

a hive body, except it is not as deep. The super is implemented to give

the bees storage space for honey that may be taken by the beekeeper, or

as food for winter. A super with 10 full frames of honey will weigh close

to 40 pounds, perhaps more.

Honey is removed from super frames by shaving off the caps with a sharp

knife--a heated knife is even better--and forcing it out of the comb onto

the sides of a cylindrical container with an inner works that spins. Empty

drawn comb of the super is placed back on the hive, hopefully to be repaired

and refilled.

Beeswax caps removed from the frames of honey are drained and the wax

is used in many ways, including beeswax candles.

Oh, yes! More on Mr. Thomas's "loading dock theory." As he explained

it to me, bees are a lot like the workers on a loading dock. When there

is work to be done, the bees work like the workers loading or unloading

trucks. But when the honey flow slows in the hot part of the summer, there

is less nectar to process . . . less work . . . so they sprawl on the front

of the hive and rest. The big difference, according to Mr. Thomas, is that

bees don't smoke cigarettes, sip soda pop, or whistle at pretty passersby.

Bees In My Bonnet

Click on images for enlarged view.

When

bees swarm they are looking for a new home, but to find this new abode

they first settle on some convenient object (trees and shrubs are good

bets) and send out scouts looking for a suitable place to call home. Each

worker bee (the females) in a swarm has a full tummy of honey which is

used to carry the new colony over for a few days. This swarm settled to

rest in a tree in my side yard. When

bees swarm they are looking for a new home, but to find this new abode

they first settle on some convenient object (trees and shrubs are good

bets) and send out scouts looking for a suitable place to call home. Each

worker bee (the females) in a swarm has a full tummy of honey which is

used to carry the new colony over for a few days. This swarm settled to

rest in a tree in my side yard. |

To

catch the swarm, I go up a ladder and shake the bees off into a box that

hangs from the end of a long bamboo fishing pole. The swarming bees cluster

around their queen and await word from their scouts before moving on to

more permanent quarters. To

catch the swarm, I go up a ladder and shake the bees off into a box that

hangs from the end of a long bamboo fishing pole. The swarming bees cluster

around their queen and await word from their scouts before moving on to

more permanent quarters. |

I

come out of the woods with the swarm in a box . . . Size of the I

come out of the woods with the swarm in a box . . . Size of the

box

needed will depend on size of swarm . . . |

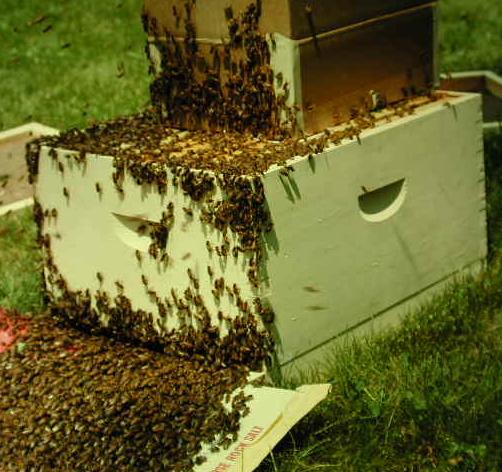

With bees poured out on plastic salt bag at front of empty hive, box is

turned upside down to allow atragglers to enter from the top. Turning box

of bees upside down gently on top of hive also will work. beeswax foundation

in inner frames will most often lure bees into their new home if their

queen is there.

With bees poured out on plastic salt bag at front of empty hive, box is

turned upside down to allow atragglers to enter from the top. Turning box

of bees upside down gently on top of hive also will work. beeswax foundation

in inner frames will most often lure bees into their new home if their

queen is there. |

Queen

bee, the long bodied bee at center of picture, deposits eggs in beeswax

cells of inner frame of hive. Queen is attended constantly by worker bees

(all females) . . . worker bees place pollen and honey in cells with eggs,

then seal the cells with beeswax . . . when eggs hatch and developinto

young worker bees, the young bee chews its way out of cell and joins the

colony as its wings and other features develop . . . Queen

bee, the long bodied bee at center of picture, deposits eggs in beeswax

cells of inner frame of hive. Queen is attended constantly by worker bees

(all females) . . . worker bees place pollen and honey in cells with eggs,

then seal the cells with beeswax . . . when eggs hatch and developinto

young worker bees, the young bee chews its way out of cell and joins the

colony as its wings and other features develop . . . |

When

bee colony needs a new queen, a peanut-shaped queen cell (perhaps more

than one) is fashioned from beeswax and a frewsh worker egg is placed therein.

Special food, called royal jelly, is placed in the cell and this rich diet

helps the egg and ensuing larva develop as a queen . . . To avoid swarms,

beekeepers eliminate queen cells before they develop . . . When

bee colony needs a new queen, a peanut-shaped queen cell (perhaps more

than one) is fashioned from beeswax and a frewsh worker egg is placed therein.

Special food, called royal jelly, is placed in the cell and this rich diet

helps the egg and ensuing larva develop as a queen . . . To avoid swarms,

beekeepers eliminate queen cells before they develop . . . |

Bees

must fly occasionally in winter to rid their bodies of waste Bees

must fly occasionally in winter to rid their bodies of waste

materials

. . . in the dead of winter (when air temperatures are well below freezing),

the bees of a colony are clustered around the queen . . . bees on the outside

of the cluster flap thweir wings to create heat . . . when the queen starts

laying eggs in late winter the temperaturwe in the hive must be kept well

above freezing . . . Bees on the outside of the cluster eat honey from

the previous year . . . others fast . .. |

My

first frame of clover honey from my first hive (background) was an exciting

moment . . . My

first frame of clover honey from my first hive (background) was an exciting

moment . . . |

|