| November

I remember--and cherish--a lot of things about Novembers, not the least

of which are the things I see and hear from deer stands between the first

pink of day and the throes of a fire-engine red sunsets.

But if I had to stop the wheels of memory on one November--one incident--I

guess it would have to be sunrise on Monday morning in 1941.

The scenario for this memorable incident started the day before--a cool,

but bright and beautiful Sunday afternoon at Crothersville (Sweet Jackson

County).

William Branard (Jack) Cain, one of my squirrel and quail-hunting mentors,

and I were soaking up sun on one of the liar's benches (there were several)

at the corner of the only stoplight in Crothersville.

To turn this into a story I must tell you that Jack, as he was known

by hundreds of people who didn't know he had another name, had taken me

under his wing when I was about 11 years old (as we later would figure

it). Jack was one of the older men of the town who had been approved by

my father as a companion when I would go to the woods for squirrels. I

could take my little Springfield single-shot, bolt-action rifle out with

my dad, Jack and a few other people, but I was not to take the rifle out

with other kids.

Our squirrel hunting relationship quickly embraced bird (quail) hunting

because Jack's brother, the late Alton Cain (one of the best bird-dog trainers

I have ever known), was putting finishing touches on a black-splotched

dropper named Duke. Incidentally, Duke was

"paws-down" be best bird dog I ever shot over (hunted with)

Perhaps, in case you are wondering about the terminology, "dropper,"

I should explain that there are many breeds of pointing dogs, English setters

(long hair) and English pointer (short hair) being the most common, at

least in Indiana. The dropper is a crossbreed of the two, usually with

short hair and a nose that detect an old overshoe or a snapping turtle

at 20 paces.

So on with my story.

It must have been November 10 as Jack and I enjoyed this beautiful fall

afternoon because the upland game (including quail) seasons always opened

on November 11, Armistice Day, (now Veterans Day) in that era.

Jack noted that the bird season--bird meant Bobwhite quail in Indiana

in those wonderful post-depression days--opened the next day and he thought

it would be good if we could hunt together.

He explained that he had been called by Uncle Sam to take a physical

examination the following Thursday for possible induction into the Army.

"If I pass the physical, they probably will take me that day," Jack

said in explaining the gravity of the situation. "Tomorrow could be the

last time we will get to hunt together."

Jack said I should ask my parent if I could take the day off from school

to hunt with him.

I told Jack that my father--great outdoorsman that he was--would not

allow

me to skip school to hunt. I told Jack I would not broach the subject

with my parents that night, and there the episode appeared to end.

But I didn't end there.

Next morning, just after daylight, I was dressed for school and breakfasting

at the kitchen table. My mother was busy at cooking on the old wood-burning

stove, which made the kitchen warm as toast even on this frost-filled morning.

"Tap! Tap!" There was a tapping sound at the kitchen door to the back

porch.

My mother opened the door to find Jack standing there in hunting togs.

And sensing, I think, that there could be some kind of conspiracy about,

she invited Jack in and poured him a cup of coffee.

As Jack sipped his coffee he poured out the story about his Thursday

Army physical exam, pointing out at the end that this could be the last

time we would get to hunt together.

My mother was sympathetic, but she exercised good judgment in pointing

out that my dad had already left for work and that she would not take the

responsibility of telling me I could skip school to hunt.

How about this, Jack countered. I could dress for hunting, stop at the

school on the way out of town, and put the matter in the hands of the high

school principal.

If the principal did not approve, I would have plenty of time to return

home, change clothing and get to school for the first bell.

My mother bought that plan. Enter Eugene B. Butler, one of my all-time

great educators, although we occasionally had our differences.

Mr. Butler was a firm disciplinarian but as fair as a man could be.

Looking over his shoulder as he entered the school's back door to see Jack

and me walking onto the school grounds with shotguns under our arms and

Duke swinging on his chain he must have known what was in the works.

He met me at the top of the wide stairway to listen to my story. I went

through Jack's spiel almost as well as he did it, pointing out at the denouement

that this could be the last time two good friends could hunt together.

I may have added that anything could happen in a war.

Mr. Butler's face got very red--like it did when he was into heavy discipline.

I was thinking that I not only would have the plan blow up in my face,

but that I might also be whomped on the spot.

But suddenly a huge smile split his face and Mr. Butler said he could

not tell me I could take a day off from school to hunt. He quickly added

that if I were not there, he would know where I was.

I ran down the stairway, out the back door and we headed east into farm

fields and best Bobwhite habitat I have ever seen

The sun was still low on the horizon and we could hear the "Hoot . .

. Hoot" of a B&O freight train 20 miles or more to the east.

Duke found the first covey at the old apple orchard on the north side

of the school's baseball field. But we fired no shots at these birds, used

primarily for training Duke.

I don't remember how many coveys we put up that day--nor how many birds

we killed. But we were back well before dark with enough game to feed our

respective households

My story could have ended there, too. But it didn't.

Next morning when I entered the school's north entrance and went up

the wide stairway to the second (high school) floor Mr. Butler greeted

me at the top with a smile as he handed me a neatly folded slip of paper.

When I was around the corner and out of sight, I unfolded the paper

to read the terse message: "Sing's absence on Monday was excusable. If

he missed any important work, he should be allowed to make it up."

|

Duke

makes a high point in the only picture I have ever seen of the dog. |

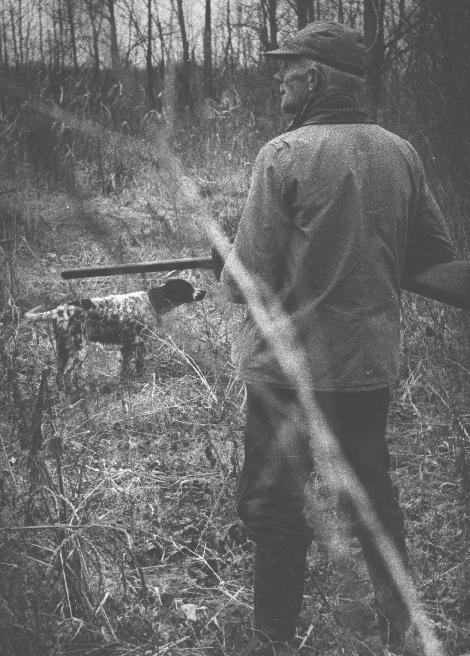

| Jack

Cain closes in to flush birds for my old dog, Pokey, many years after Duke

was gone to Bird Dog Heaven. |

|

MORE

JACK & DUKE STORIES

One year (after WW II), when Duke was getting up in years, Jack and

Alton got so busy that they didn't have time to condition the old dog on

the Old Orchard covey that frequented the big ragweed patch behind their

house.

Jack, Alton and their mother lived only a few houses north of the school

and the big ragweed patch came right to their property line. It was the

best of all locations for the owner of a bird dog.

Opening day dawned bright and sunny with temperatures far above normal.

And Jack, knowing that Duke was not hardened to the rigors of running,

said we would stay fairly close to town.

Our hunt started early and we never made it to the Muscatatuck River

bottoms because Duke conked out on us at mid-afternoon when we were headed

back to town. The old guy had given it all he had and simply could move

no further.

Although I didn't own a real hunting coat until later in life, Jack

wore a duck coat with a deep game bag all the way across the bottom of

the back.

We put all of our birds in my makeshift hunting coat (an old denim "Jimslinger"

with a game bag fashioned by cutting slits in the muslin lining).

We placed Jack's hunting coat flat on the ground and manage to get Duke

in the game bag, upside down; back feet and legs and tail protruding from

one side, a smiling dog head and front feet from the other.

We took turns wearing the coat all the way to town, and we learned a

valuable lesson on the importance of conditioning of dogs prior to opening

day.

HOW GOOD WAS

DUKE?

VERY, VERY . . . Take my word for it. Jack and I would both shoot on

covey rises, but we would take turns on singles. The non-shooter simply

backed up the shooter. He could not shoot unless the shooter missed.

One time we had a huge covey of birds scattered in Roy Chasteen's thicket

in the Muscatatuck River bottoms east of C-ville.

Duke went on point--apparently a single--in a thick carpet of leaves

from a circle of white oak trees that covered an area as big as a house.

To complicate the issue, the trees were covered with wild grape vines

and it appeared the only place that bird could go would be through a small

opening in the jumbles limbs of the canopy.

Jack, at least 25 years my senior, said it was my shot, but I knew it

wasn't. I knew he wanted to see how a snot-nosed kid would handle the situation.

So I waded into the leaves to flush the bird. which went--as I thought

it would--through that opening at what seemed the speed of light.

Flabbergasted as I was, I managed to punch out a shot just as the bird

went through the opening.

Jack slapped his thighs and roared with laughter.

When he regained control, he told me I hit that bird.

There were no falling feathers . . . nothing to indicate I had made

a lucky shot . . . and I opined that my pattern wasn't even close.

Jack said he thought I hit the bird and that Duke concurred. Duke thought

you hit it," Jack said, pointing out that the bird had flown high over

an adjacent field and into the next thicket.

"Duke took off in the direction the bird went," Jack said. "Let's just

wait here until he comes back."

You guessed it. In a few minutes, Duke returned with my bird in his

mouth, not a feather ruffled.

WHAT A LAZY PUP

Duke must have been four or five months old when I met him on a bright

summer-Sunday morning.

I had walked east in the alley from our house (three or four blocks)

to talk with Jack, and when I rounded the corner of the house this pup

was flaked out on the weathered boards of the back porch in a swath of

sun.

Jack's mother told me Jack was not home, but that he would be

back soon . . .that I could wait.

I waited for a few minutes, but decided to leave and come back later.

As I walked past the sleeping pup, I crossed his front legs behind his

head.

A couple of hours later I returned. Jack was home and Duke still slept

. . . his front legs crossed behind his head.

X MARKS THE SPOT

It was inevitable that soon after returning from the U.S. Navy for a

four-year stint of WWII I would get into the bird dog business with a dog

of my own.

Rex was an older English setter. He didn't measure up to Duke on his

best day, but he was a good dog on his own and contributed greatly when

hunted with Duke.

Jack and I would start conditioning the dogs once or twice a week well

before the season opened.

One Sunday morning we had the Apple Orchard covey scattered in the ragweed

field behind his house. There was a low, woven-wire fence running north-south

a few yards into the weeds.

Both dogs were "birdy" on a single. Duke jumped the fence and went on

a half-squat point when he hit. As we slowly approached to flush the bird,

Rex jumped the fence from the other direction and was on a high point when

he hid--his front feet on one side of Duke and his back feet on the other.

"X marks the spot," Jack said wryly as we drank the picture down like

ice-cold lemonade on a hot day.

|