July

Don't ask me for the whys and wherefores, but

among setline anglers July has always been known as big catfish month.

It may be that flathead catfish, channels and

blues--the stars of the Hoosier big cat drama--have taken daytime refuge

in deep holes of rivers or under log jams and other heavy cover near deep

water when days grow hot and long.

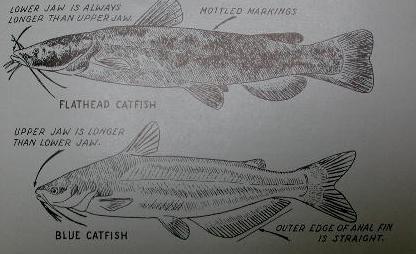

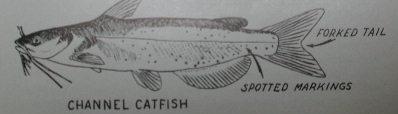

| The

accompanying Department of Natural Resources illustrations will help cat

lovers identify the big three cats of Indiana waters. Note that the channel

catfish also has a rounded edge on the anal fin . . . this helps separate

channel and blue cats. |

|

|

|

Whatever the reason, July certainly is the real

beginning of the setline season. And big live bait is the key to success.

One of my fondest memories of setline fishing

unfolded to my utter amazement at Calford Bayou (Vernon Fork of the Muscatatuck

River) when I was about seven years old.

My dad, who had to work to make a living in those

post-depression days, would set his lines on Saturdays with the hope of

catching a big cat. Success meant a Sunday fish dinner for our family and

often the neighbors. The only refrigeration we had was a big old icebox

and that would not preserve fish more than a day or two.

Not having a boat at our disposal--nor even a

method of transporting a boat if we had one-- my dad used what he called

"throw" and "bank" lines. The difference between the two was that the throw

line usually consisted of a strong main line of 20 feet or more and utilized

four to six strong hooks, each attached to the main line with a drop line

that was about a foot long. The main line (mudded to make it less visible

to anyone who might be on the river) was attached to strong, underwater

objects (most often a strong tree root), and the weight (most often a rusty

railroad spike) was attached to the other end of the main line.

With the line attached and hooks baited with

live long-eared (redbelly) sunfish, my dad would stretch the line, swing

the weight pendulum style, and heave it into the river.

Bank lines usually were attached to sturdy poles.

They usually were armed with only one or two hooks and often were positioned

to keep the live bait flouncing on the surface of the water.

Aside from the fact that my dad liked to make

his vast outdoor knowledge available to me, he liked to have me along on

his setline trips because I was pretty good at catching redbellies on a

pole and line.

With tobacco cans of garden worms in our back

pockets, we would walk to the river early in the afternoon and spend the

rest of the day catching bait. My dad usually opted for dead ash poles

because they were straight, strong and light.

Our fishing line (usually a silk braid about

the same length as the pole) usually held a long-shanked, wire "sunfish"

hook and a small wrap-on sinker a few inches above the hook.

As we caught sunfish they were kept alive in

a drawstring bag he knitted from strong twine (called stagen).

When we had enough bait to fill the hooks--usually

25 to 30--we would wait for the sun to fall behind the tree-lined riverbanks

and start baiting up.

It would always be well after dark before we

got home, but our supper would always be warm on the back or the old wood-burning

stove. We would have plenty of time to think about the denizens that might

be taking our baits before drifting off to sleep until awakened well before

daylight to go "run" the lines.

My big setline moment--the one I remember best

although there are many fond ones--came on such a Sunday morning. The sun

was barely up when we approached the river half a mile below Calford Bayou

where the first of seven throw lines had been "set" in a deep hole of the

river.

To check the lines, my dad would roll up his

sleeves (shirts with short sleeves hadn't been invented in those days),

and on hands and knees would run his left hand and arm in a sweeping motion

until he found the main line. He would pull on the main line gently until

it was well above the water, and we would hope he would feel a fish pulling

back. If there was no resistance, he retrieve the line (removing the baits

and dropping them back in the river, most of them still alive.

With hooks bare and the line free, he would carefully

wrap it around the railroad spike (weight) in a manner that would cover

the points of the hooks. It would be placed in a container (usually a galvanized

bucket) for the trip home where the lines would be stretched to dry then

rewound and placed back in the bucket, ready for the next weekend trip.

On this, my most memorable setline morning, my

dad had gone through his ritual at each of six lines in six deep holes.

But nothing had pulled back. We were down to the last line.

That line was set at the upper end of the Calford

Bayou deep hole, a place where we often fished for bass with live minnows.

At first, my dad had trouble remembering where

he had anchored the line, but found it and pulled in enough loose line

to get his hand above the water. There was no resistance to that so he

gave the line a slight inward pull.

For a few seconds it appeared that Sunday dinner

(the noon meal) would be fried chicken and trimmin's which was not all

bad. But then, with the line still grasped tightly, my dad's hand and arm

was pulled back under the water.

"We got one, Bill," my dad said and brought the

fighting fish in slowly, (removing the dropper hooks with a simple pull

at each knot) until he could slip his fingers in the gills and his thumb

into the corner of the fish's mouth. Then, in a smooth sweep of his hand

and arm, he tossed the fish (still hooked) into the weeds well away from

the water.

The walk home through the woods and fields did

not quite measure up to my expectations because I wanted to carry the fish

and it was so long that its tail dragged the earth when I held it.

"You can carry it when we get to town," my dad

promised, and he lived up to his word although he had to help me get it

draped over my back.

It was a 16-pound blue, but more than that it

was a big Sunday dinner for our family and some of the neighbors; not to

mention the notoriety residuals that ride the shirt tails of small town

anglers who catch big fish, some of which may not be known for many years

. . . if ever.

Like, for example, many years later I am recalling

my big cat moment in a conversation with my squirrel/quail-hunting mentor,

the late Jack Cain.

Jack said, he had been standing on the corner

that morning when Sampson Mitchell (the town police department) walked

past and said: "Jake Scifres and his little snot-nosed kid, just walked

past my house with a big catfish."

|