| November

When Mr. Frost points November at Hoosierland,

myriad hunting scenes twirl through this old head like cherries, oranges

and lemons on a river-boat one-arm bandit. When they stop, the little window

always is graced by three identical scenes . . . straight across.

There is no outpouring of coins, or gamblers catching

them in their baseball caps. But my jackpot comes in a flood of birds,

hunting, bird dogs and the men who trained and hunted them.

It is not difficult for me to conjure up such

memories when the frost flies.

So November, in my book, is bird (quail) hunting

in Southern Indiana with a good dog and my favorite shotgun. Thus, I want

to think of this column as a tribute to every bird dog--pointers, setters,

et al--that ever developed a temporary case of rigor mortis while sniffing

birds.

Sure, a phalanx of deer, ducks, rabbits, squirrels,

and a host of other game birds and animals march across my November proscenium.

But the scene of the hunter with the blunderbuss and the bird dog is the

one that sticks in my mind.

Starting with the great Fishel’s Frank, an English

pointer field trial champion in the early 1900s, Hoosier bird dog enthusiasts

have bred and trained literally hundreds of championship bird dogs, or

dogs of that quality. While Frank, bred and campaigned by Hope (Bartholomew

County) industrialist U. R. Fishel, did not win a national championship,

he beat many dogs with such credentials.

|

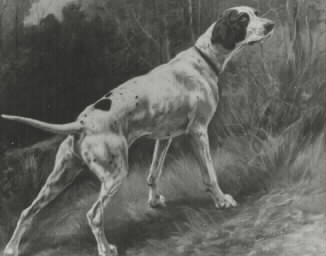

Fishel's

Frank, an English pointer bred and campaigned in the early 1900s. Frank

died in 1916 at the age of 12 and has been called the most renowned dog

in the world. |

Frank is said to be buried at Hope, but there

is no stone to mark the spot, nor can any resident of this town pinpoint

the spot where Indiana’s greatest claim to bird dog fame lies.

But the dog that sticks out as the greatest I

ever hunted over--and perhaps as good, or better than the great champions--was

a dropper named Duke.

A dropper, if you are not familiar with the term,

is neither an English pointer nor an English setter. It is an offspring

of cross breeding of the two, most often having the short hair of the pointer.

Duke was such a dog, black splotches on a body

of short, white hair. But to dismiss Duke with this scant description would

be a fallacy of high order.

I met Duke as a gangly pup of three to six months.

He was owned by the late Alton Cain, brother of the late William Branard

“Jack” Cain. Alton and Jack, two of the best outdoorsmen Crothersville

ever produced, lived with their mother on the east edge of the town . .

. and I do mean the edge of town.

Their back yard ran smack-dab into a huge field

of white top, foxtail and other weeds (including ragweed, the seed of which

is a favorite food of Mr. Bob). This magnificent weed patch ran all the

way to the Fairgrounds woods on the north and to an ancient apple orchard

on the south.

Of course, this field hosted one big covey of

quail every fall, perhaps more.

As the years rolled past we did not shoot these

birds much, just enough to keep them healthy. They were our dog-training

birds.

My first meeting with Duke came on a bright, warm

spring Sunday morning. I had walked east from our house some three blocks

to talk with Jack who was one of my older squirrel-hunting mentors. At

that point in my life I could hunt by myself or with a few select older

men, Jack being my favorite when my dad wasn’t available because of work.

When I went to the back porch looking for Jack,

the first thing I saw was this skinny puppy . . . sound asleep in the sun.

Jack’s mother told me he wasn’t home . . . that

he would return in an hour or two. I started to leave but not without saying

hello to the pup.

Sitting down next to the pup on the weather-beaten

floor of the back porch, I scratched gently at the base of his ears. He

opened an eye, groaned and went back to sleep.

For several minutes I talked with this laziest

dog I had ever seen, then left him there with his reveries. Before leaving,

I pulled both front legs behind Duke’s head and crossed them at the ankles.

I left him in that position.

Some two hours later--almost noon--I returned

. . . to find Jack still among the missing, and Duke still fast asleep

in the sun--his front legs still crossed behind his head.

In my mind, Duke never escaped his lazy image.

But under the tutelage of Alton, who likewise was the best bird dog trainer

I ever have known, Duke became a first class bird dog.

On most occasions when I hunted with Jack and

Duke, Alton was working. But on the few occasions when I got to see Alton

handle Duke in the field, his success at getting optimum effort out of

Duke came quickly to the fore.

If Duke flushed a bird, or committed some other

grievous bird-dog error, Alton (with soft, gentle words) would call him

in and gently pinch an ear, with such a reprimand as: “That was bad, Duke

. . . you’ve got to be more careful.” Duke heeded his master’s words .

. . and Jack’s words, too.

Jack, in his early 40s at the time, introduced

me to bird hunting with Duke after asking my dad if I could hunt birds

with him. He had a double barrel 12-gauge I could use. Later, we would

determine that I must have been about 13 years old when he got me started

in this wonderful activity that provided such great food for the table

in those days at the end of the Great Depression, days when it was great

just to have food on the table. Quail baked in a pan of dressing was a

great escape from a diet of beans ‘n taters.

When Jack and I hunted with Duke, which was at

every opportunity, we would both shoot on covey rises. Then, as we followed

the birds for that good singles gunning, we would take turns, the non-shooter

being permitted to shoot only if the primary gunner missed, or if there

were more than one bird.

One time we had scattered a big covey of birds

in the north end of a Muscatatuck River bottomlands thicket. We were taking

turns as Duke pointed the singles.

I had just had my turn when Duke locked up in

a beautiful, but very difficult setting. There was this circle of white

oak trees that covered an area 40 or 50 yards in diameter. The trees were

covered with wild grape vines even up into this beautifully natural canopy.

Duke was frozen solid--he looked as though he might be there for the winter--and

the bird obviously was very close to his nose in dry leaves that must have

been a foot thick.

“It’s your turn,” Jack said as we approached Duke

from the rear.

I reminded Jack that I had just missed a bird

. . . that it was his turn. But he insisted otherwise and I realized he

wanted to see what this young upstart would do with this situation. I accepted

the challenge.

Easing in to flush the bird, I wondered where

it might go . . . through the walls of grape vines? Not a chance.

After several seconds of moving my boot through

the leaves, a fat Bob rocketed straight up. I had to shoot as the bird

blasted through a small opening high in the grapevine canopy.

“I didn’t touch a feather,” I declared as Jack

laughed and slapped his thighs.

But when Jack stopped laughing, he told me I had

hit the bird.

“I think you hit that bird so did Duke.” Jack

said. “He (Duke) watched the bird after it cleared the tree tops . . .

then he took off in the direction the bird had gone (toward another thicket

200 yards to the east).”

“Let’s just stand here until Duke comes back,”

Jack said.

Duke came back about 10 minutes later . . . with

my bird in his mouth.

A prevailing philosophy in those days noted that

every man deserved to own one good bird dog in his lifetime. Those who

qualified started running their dogs in conditioning workouts as soon as

the heat of summer dwined and weeds started dying.

Duke’s pre-season conditioning usually occurred

in the big weed patch behind Jack’s house.

A little later in life--when I stepped into the

bird-hunting scene with my own dog (an English setter named Rex)--Jack

and I would run the dogs on Sunday mornings. Rex and Duke worked beautifully

together.

There was this low, decrepit and rusty, woven

wire fence along the edge of the field and the dogs often gracefully leaped

it when birdy (working birds).

One time Duke jumped the fence and went on a staunch

point when he hit in the weeds on the other side.

We took our time getting there to flush the birds.

Before we got there, Rex jumped the fence from another direction and settled

crosswise atop Duke.

“X marks the spot,” Jack said.

It would be an experience neither of us would

ever forget.

One year--probably the fall of 1941--Jack and

Alton had been so busy that Duke’s pre-season conditioning had been somewhat

lacking. As a result, Duke was not hardened to the rigors of hunting.

Alton had already been called for duty in the

Army, and Jack was scheduled to take his physical for induction three days

later (a Thursday).

The season opener (November 11) would be a Monday,

and on Sunday afternoon Jack invited me to go bird hunting the next morning.

If he passed his physical, they might take him immediately, he said.

“It could be the last time we will be able to

hunt birds together for a long time . . . maybe forever,” he said.

I explained that I would rather go bird hunting

than do anything else . . . but it was a school day . . . I would have

to go to school.

Jack suggested that I try to get permission to

go hunting from my parents, but I was afraid to even try that.

When the sun, like a gigantic red ball in the

east, ushered in a beautiful, frost-filled day, I was having breakfast

at the kitchen table. There was a knock at the kitchen door, and my mother,

the late Laura Belle Scifres, opened the door to find Jack (in his hunting

togs) shifting from one foot to the other.

Jack came in and my mother poured him a cup of

coffee.

Jack went through the story about his Army physical

and ended it by asking if I could skip school for a bird hunt.

“No!” she said, explaining that my dad (the late

Jacob W. “Jake” Scifres) had already left for work, and that she could

not approve the plan.

Not accepting this temporary setback, Jack outlined

a plan which would call for me to get dressed to hunt, and the two of us

(guns, dog and all) would stop at the school (right next to the apple orchard)

to try to gain the approval of Eugene B. “Gene” Butler, a firm disciplinarian

and principal of the school. If that failed, I still would have time to

get back home, change clothing, and go to school.

This seemed reasonable enough, my mother said.

Mr. Butler was entering the back door of the school

when we arrived. We stacked the guns against a maple tree and Jack held

Duke’s chain as I went in the back door and up the wide stairway to Mr.

Butler’s office. Mr. Butler was busy with arranging his office for a day

of school, but he listened politely as I blurted out the story of Jack

facing his Army physical exam, the possibility of being called into service,

and how he would like for me to go bird hunting with him.

When Mr. Butler was upset and angry, his face

turned red. It was red when I finished my story. I feared not only that

Mr. Butler would nix the plan, but that I might also be whomped . . . then

and there.

But suddenly a large smile spread across Mr. Butler’s

face.

“I can’t tell you to stay out of school to go

bird hunting, Sing (my nickname),” he said. “But if you are not here today,

I will know where you are.”

Duke found the apple orchard covey a few minutes

later, but we didn’t shoot them. There would be plenty of shooting in the

Muscatatuck River bottoms; so much, in fact, that we would run out of shells

at mid afternoon.

It was a blessing in disguise. As we came out

of the bottomlands and headed for town, Duke conked out. He was too tired

to walk.

We couldn’t leave him. Duke was more than a bird

dog.

We both tried cradling Duke (feet up, baby style)

in our arms, but that didn’t work either.

Jack put his birds in the makeshift game bag

of my old “jimslinger” coat, and we put Duke (still feet up and with head

out one side of the game pouch of Jack’s hunting coat and his tail out

the other side. We took turns wearing the coat and giving Duke the ride

of his life back to town.

The story would end the next morning when I entered

the school on the first floor and went up the wide stairway to the study

hall.

Mr. Butler would be waiting for me at the top

of the stairway.

With a wish for a good morning, Mr. Butler handed

me a neatly folded piece of paper.

“Show this to your teachers today,” he said.

“Sing’s absence from school yesterday was excused,”

the note read . . . “If he missed any school work, he should be allowed

to make it up.”

|