| 06-03-02

Much could be said and written about the late Woodrow W. Fleming, a

high school biology teacher for 26 years, and the first (probably the only)

non-political director of our Division of Fish and Wildlife.

Woody, as friends and the scientific community knew him, died at 89

last week and was buried Saturday at Columbus' Garland Brook Cemetery.

One could write about Woody's accomplishments in wildlife conservation--there

were many. But the Woody Fleming story I choose to tell today has been

heard by few and I was privileged to hear it from the horse's mouth.

When the late Matthew Welsh became governor of Indiana in 1961, he named

Don Foltz, a western Indiana hog farmer, director of the Department of

Conservation (now the Department of Natural Resources). Woody, by chance,

was one of the candidates Foltz could choose from in naming a director

of the Division of Fish and Game (now the Division of Fish and Wildlife).

It was late on a winter afternoon when Foltz interviewed Woody--so late,

indeed, that Foltz suggested that they continue their talks over dinner

at a nearby restaurant. Indiana's political spoils system was rampant in

those day (it is alive and well today), and Foltz (presumably to test him)

asked Woody what he would do if he had to name a superintendent for the

Muscatatuck Game Farm, which was an important cog in Indiana's vaunted

artificial stocking program.

Foltz explained that there were two strong Democratic candidates for

the job of superintendent of the game farm. Their party credentials were

much the same, he explained, adding that regardless of whom he named, party

harmony would be at stake in Jennings County.

"Who would you give the job to?" Foltz asked. "I wouldn't give the job

to either of them," Woody later quoted himself, when he told me the story.

"I would close the game farm . . . and all the other game farms . . . if

you won't let me do that I don't want the job."

"He (Foltz) almost fell out of his chair." Woody told me.

The rest is history. Foltz gave Woody the job and a few months later

Indiana's massive game farm operation, which was pouring countless thousands

of dollars down rat holes, was closed amid a storm of protests from armchair

conservationists everywhere. The era of wild game stocking, per se, had

bit the dust . . . justifiably.

There are, of course, dozens of other stories I could tell about Woody

Fleming . . . like the time I flushed his first Indiana grouse on a Brown

County hillside and yelled: "Here he comes, Woody," to hear a single shotgun

blast a few seconds later and a startled Woody say: "I think I got him."

We looked everywhere for the bird without success. I finally found it

in a small lake, and if memory serves me correctly, I did some minor "skinny

dipping" to get Woody's bird--for which he dubbed me the finest retriever

he had ever hunted with.

At noon that day Woody built a nice wood fire in the fireplace of a

little cabin (on the property he owned) and (without a skillet) served

up one of the best pork chop dinners I have ever had . . . anywhere.

Another time, when Woody was introducing me to the fine fishing on the

Ohio River embayments above Markland Dam (upstream from Madison), we spent

an afternoon taking state-record spotted (Kentucky) bass, but never sought

the recognition that came with them.

When darkness came that afternoon, we turned into a little restaurant

nearby for din-din, then went back to the boat for frog hunting.Woody was

much impressed by the fact that I made 25 "grabs" that night and caught

24 bullfrogs.

"Shucks," I said modestly. "It was nothing."

I spent most of the night on my haunches in the bow of Woody's Jon-type

boat so I could catch the frogs that woody spotted with a strong light

from the rear seat while he guided the boat.

On one occasion, he spotted a big frog at water's edge, six feet or

so back under an outcropping of stone that was almost like slate. I had

to duck to get in under rocks, but I caught the frog. As woody backed the

boat out from under the stone, he stopped the boat just as my head

was a foot or so below the rocks.

I waited patiently, but the boat didn't move. Woody finally broke the

silence.

Look just above your head," Woody said, playing his strong light on

. . . a huge water snake coiled a foot above my head.

"OK," I said after a few seconds in which neither the snake nor

I had blinked, "you've had your fun . . . now get me out of here."

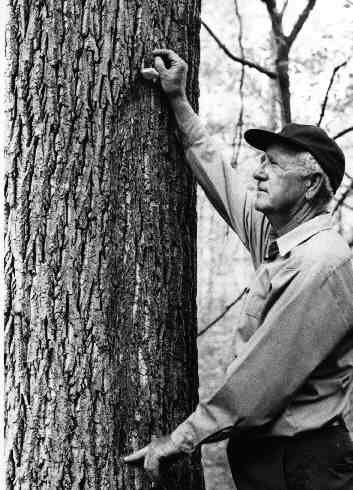

| Woody Fleming shows me

a four-foot scratch mark on a large tree (ash, I think, or yellow poplar).

Woody firmly believed the scratch mark was made by a big cat, probably

a cougar. The scrach mark started about 7 feet high on the tree and extended

downward to a point slightly below his waist. The scratch mark was roughly

two inches wide and went through roughly 1 1/2 (one and a half) inches

of bark to the wood of the tree. Woody discovered the evidence of big cats

being in Indiana as a timber manager after his years as director of the

Division of Fish an Game, in the late 1960s or early '70s. |

|

|

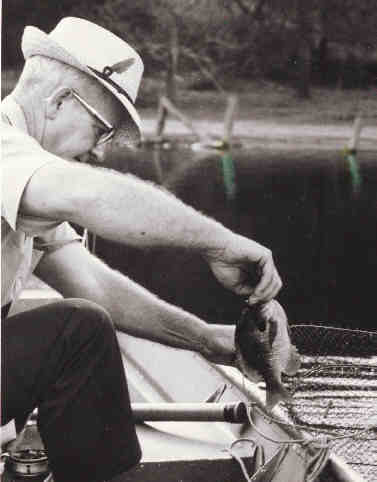

The late Woody Fleming

puts a husky bluegill in the live bag after taking it with a fly rod in

the 1970s. The fly rod was his favorite method of fishing and the bluegill

was one of his favorite fish. |

|